Podcast-series in two parts with live recordings and interviews from the Sharq taronalari International folk music biennial in Samarkand, Uzbekistan – the norwegian Folk Music Magazine “Folkemusikk”, 2020 (In Norwegian and english)

In August 2019, I had the opportunity of going to the five-day Sharq Taronalari international folk music biennial in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, to cover the event for the Norwegian folk music magazine Folkemusikk, together with friend and fellow music journalist for the occasion, Jens Lunnan Hjort. The festival was a whirlwind of impressions, both musical and otherwise, this being the twelfth iteration of a gathering stretching back to 1997. Despite its breadth – 31 musical groups with members from 33 countries participated in 2019 – the event is barely spoken of in the Global North, though ensembles from several European and North American states were present.

The festival itself is a strange blend of many things: a showcase of Central-Asian history and heritage set to the backdrop of surreally beautiful Madrasahs built between the 15th to the 17th century surrounding the main concert area on Registan Square. It is also a Grand Prix of sorts for folk music groups from all over the world, which compete for a range of prizes, despite the slight impossibility in judging widely different folk music traditions up against one another. Finally, Sharq Taronalari can also be seen as a case study in cultural “soft diplomacy” by an autocratic regime, albeit one that has slightly loosened its grip since the 2017 handover of power from long-standing President Islam to his heir-apparent, Karimov Shavkat Mirziyoyev.

Alongside the musical competition itself, there is also an academic conference, where ethnomusicologists, anthropologists and scholars of all stripes discuss issues surrounding folk music and folklore writ large. Coming from our corner of the world, where, despite the existence of a small yet thriving scene, folk music is a niche genre you have to seek out to immerse yourself in. With this in mind, what we saw in Uzbekistan, where folk songs are something that seemingly permeates society at large and people not only appreciate, but know by heart, it was a bit astounding to hear the calls of alarm at the conference, expressing unease at how folk culture would hold up in the competition for people’s attention in our interconnected and rapidly digitizing world. Your worry depends on your point of departure, it would seem.

«Det Kom Jo ingen Revolusjon» (There was no revolution), A conversation with Jenny Hval, Lester Bangs and Sue Mathews – ENO Musical Yearbook, 2015 (In Norwegian)

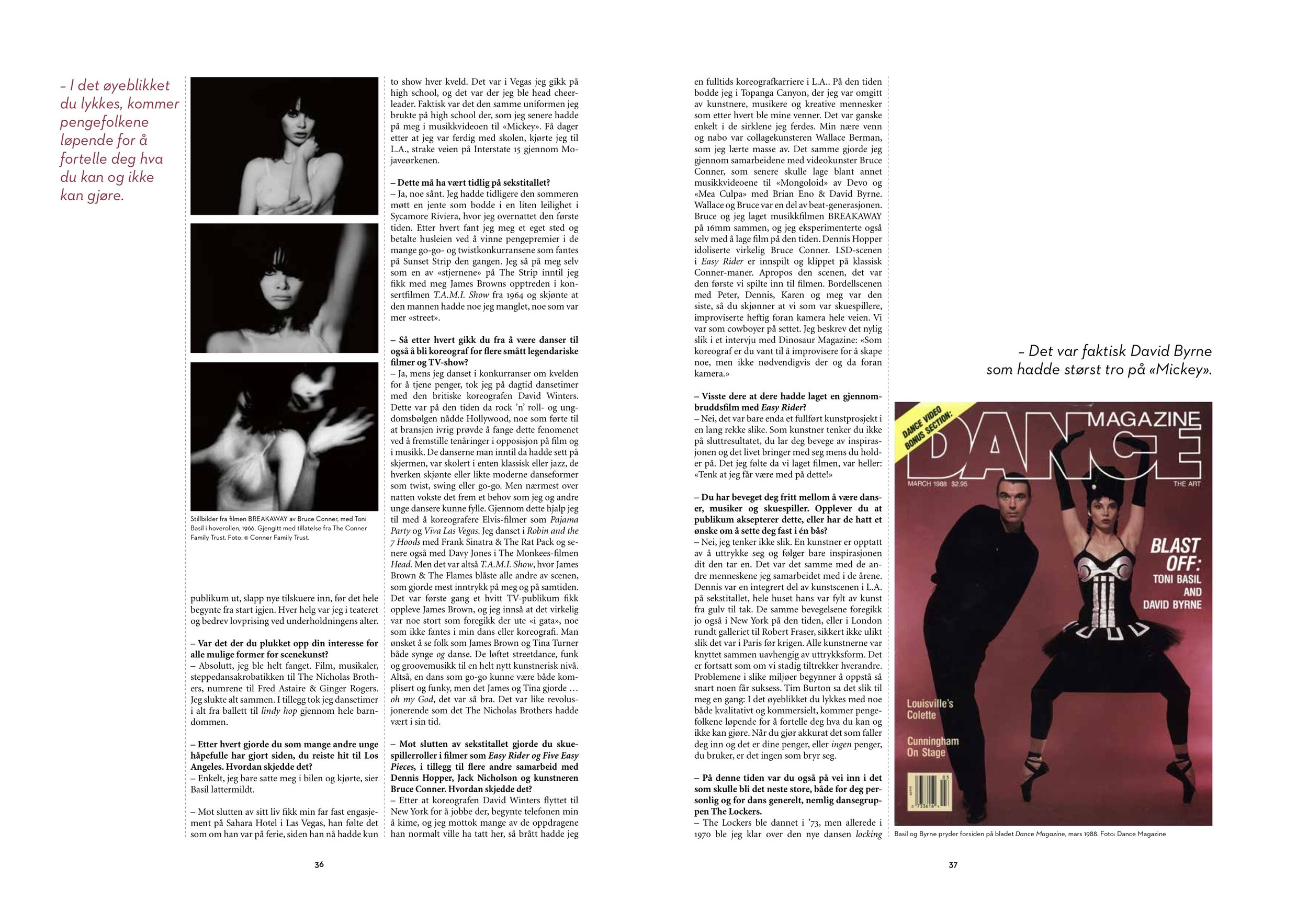

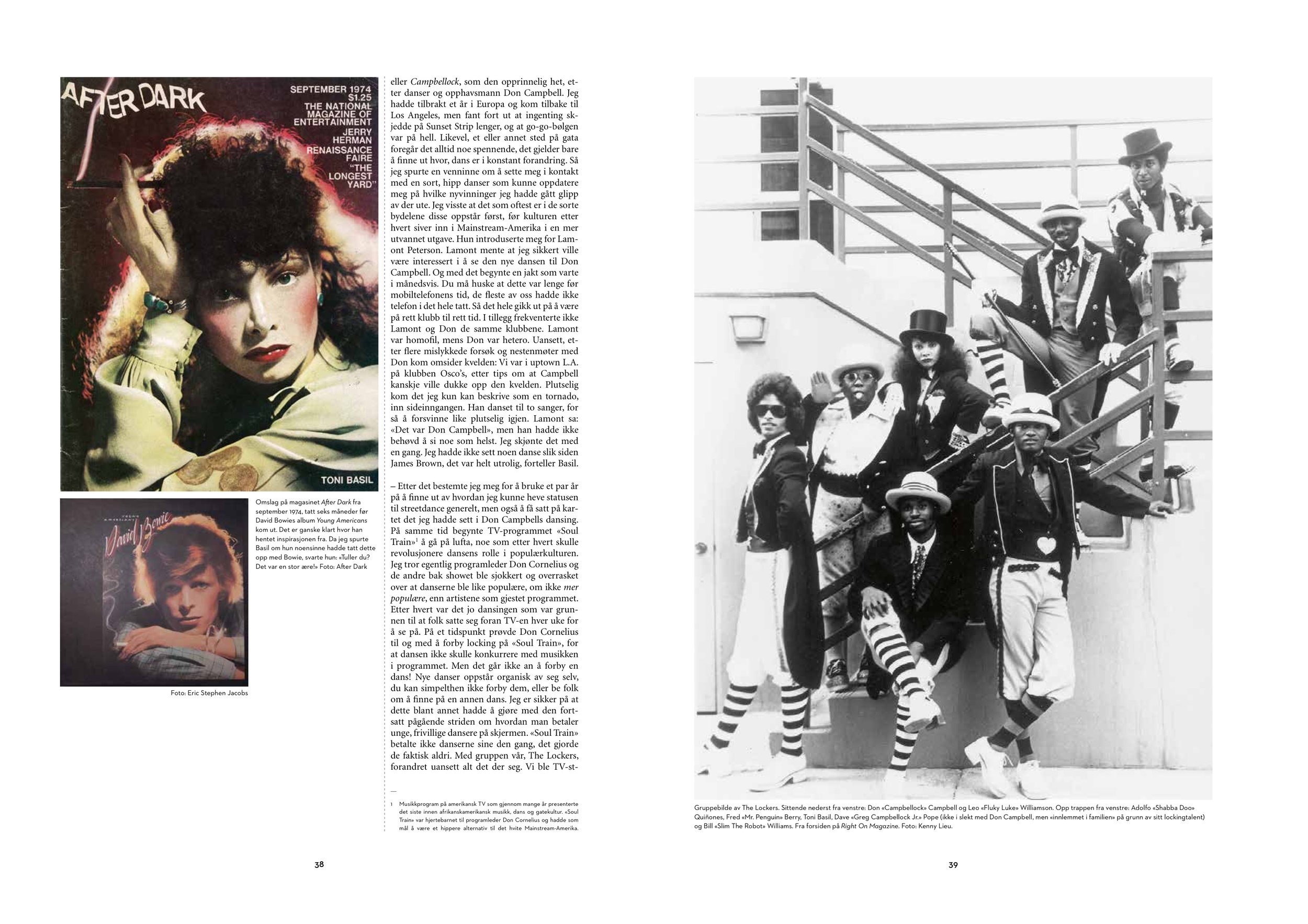

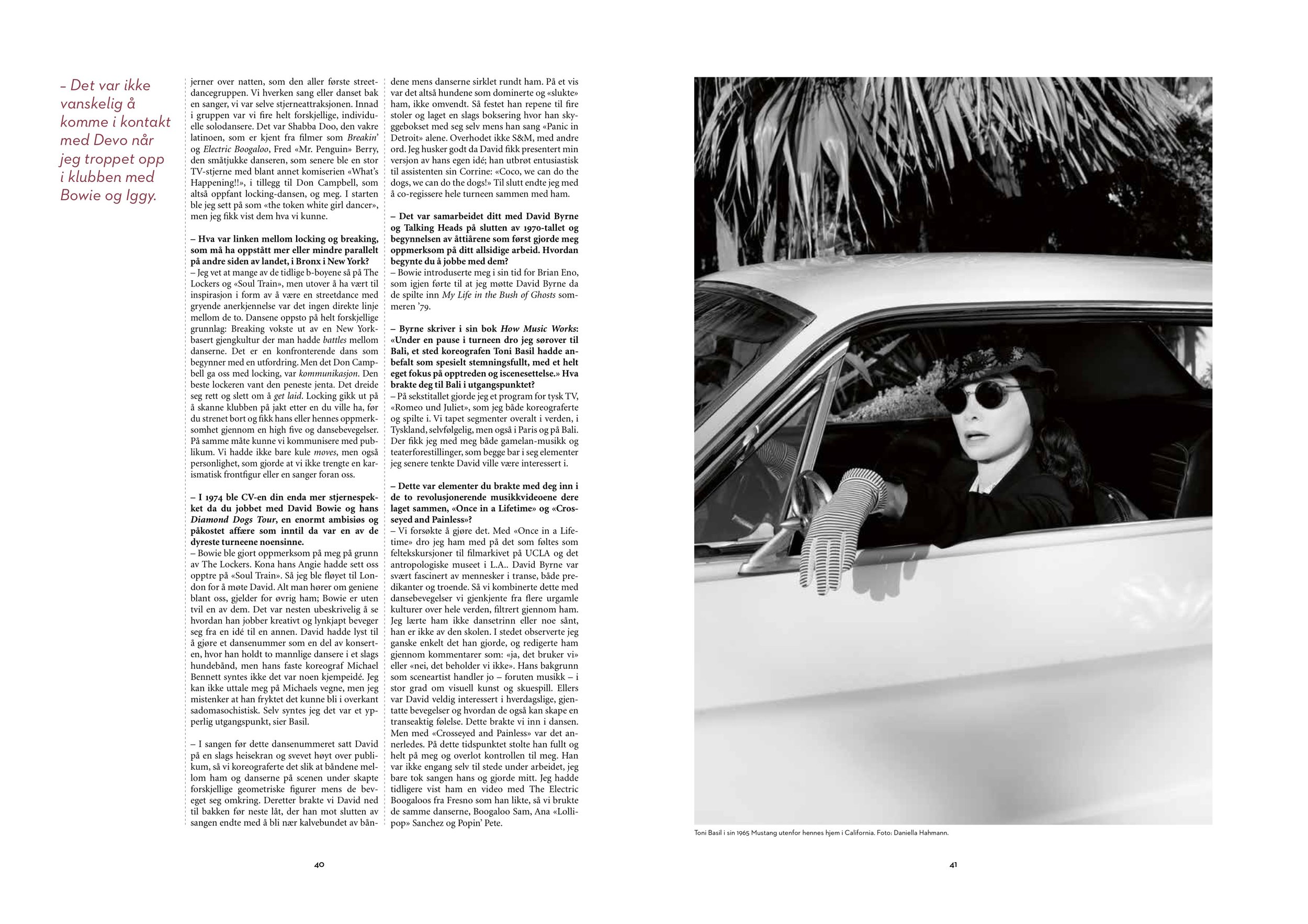

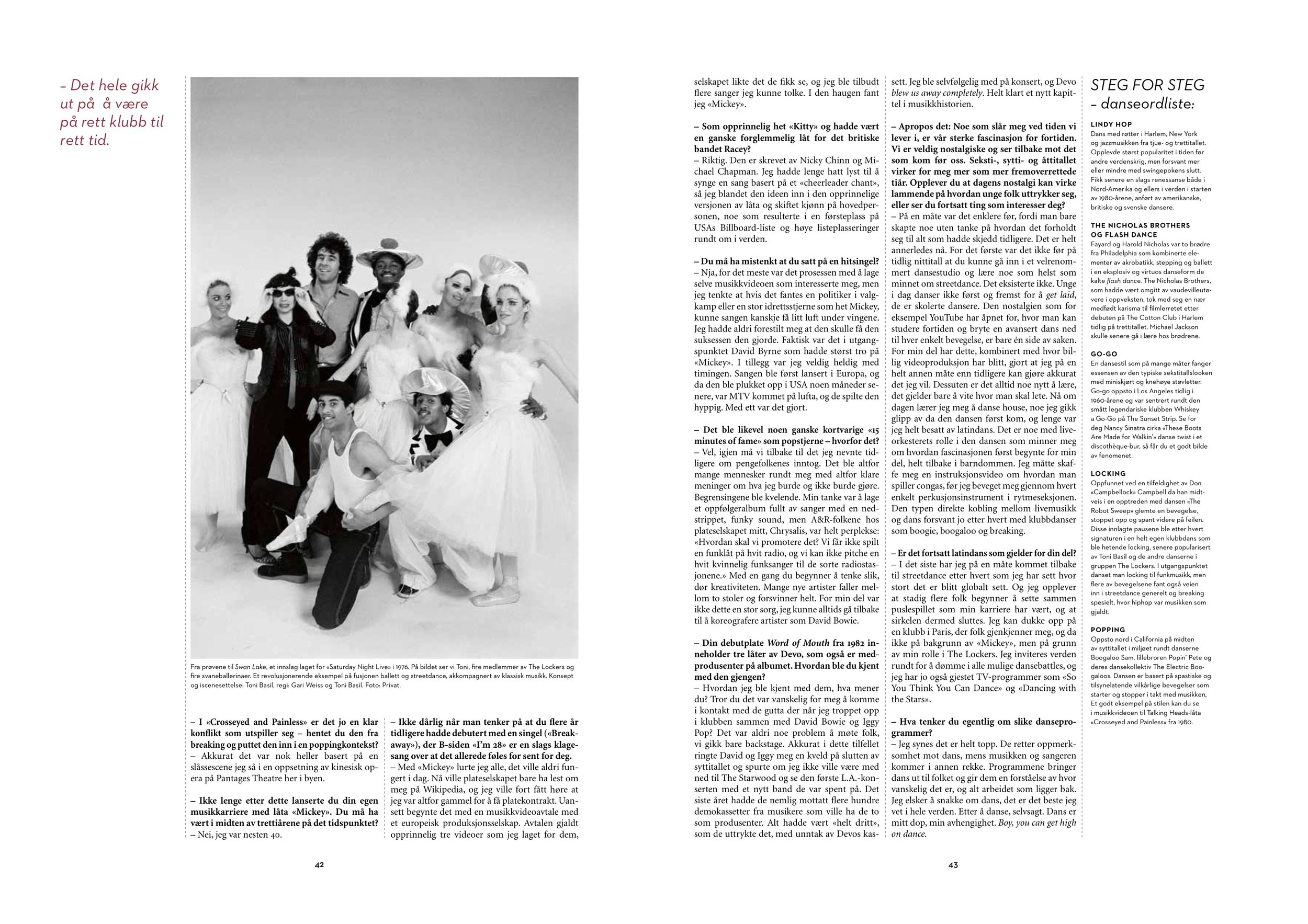

Musikk, Dans og Drama (Music, Dance and Drama), An interview with dancer, choreographer and musician Toni Basil – ENO Music Magazine, 2014 (In Norwegian)

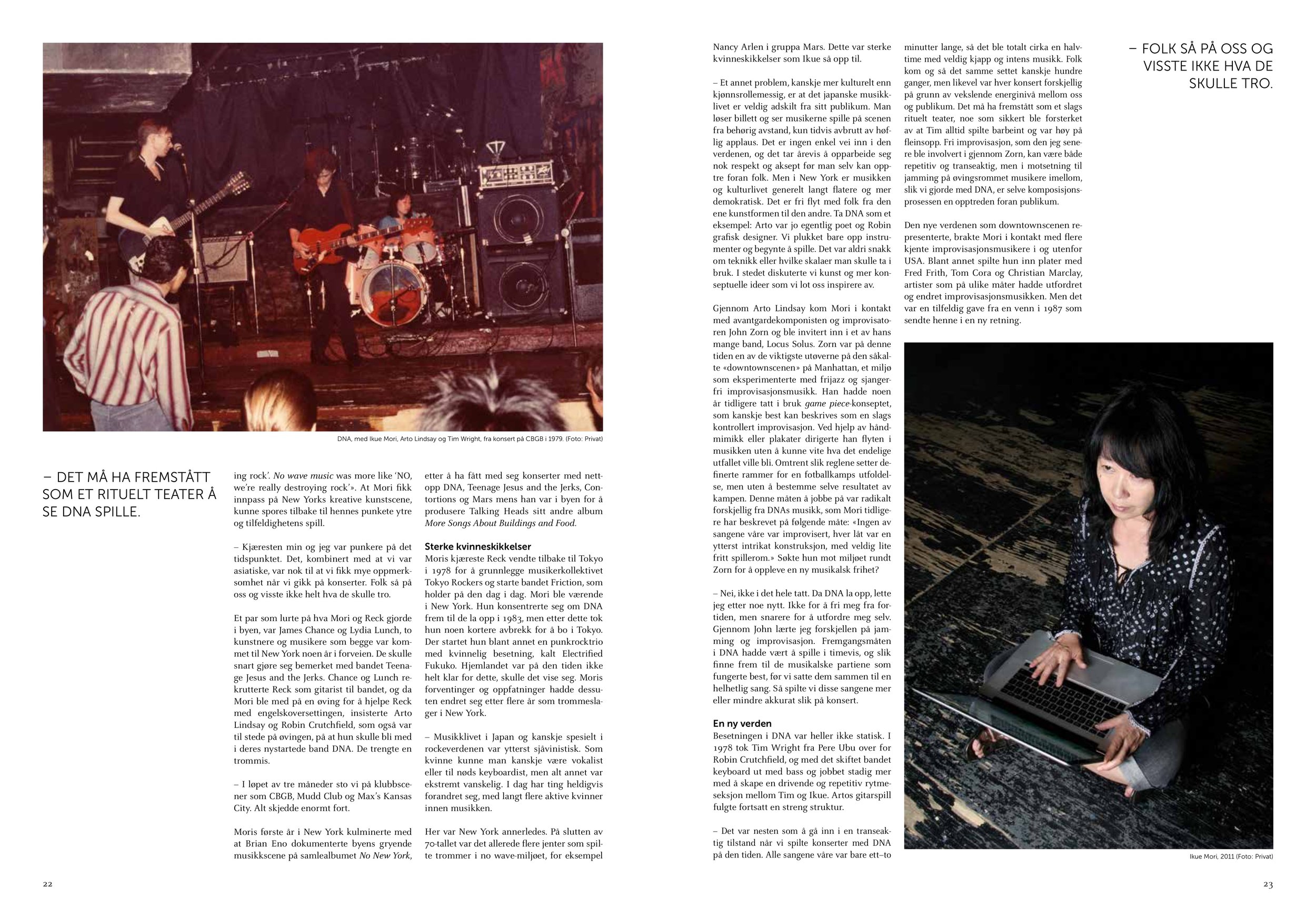

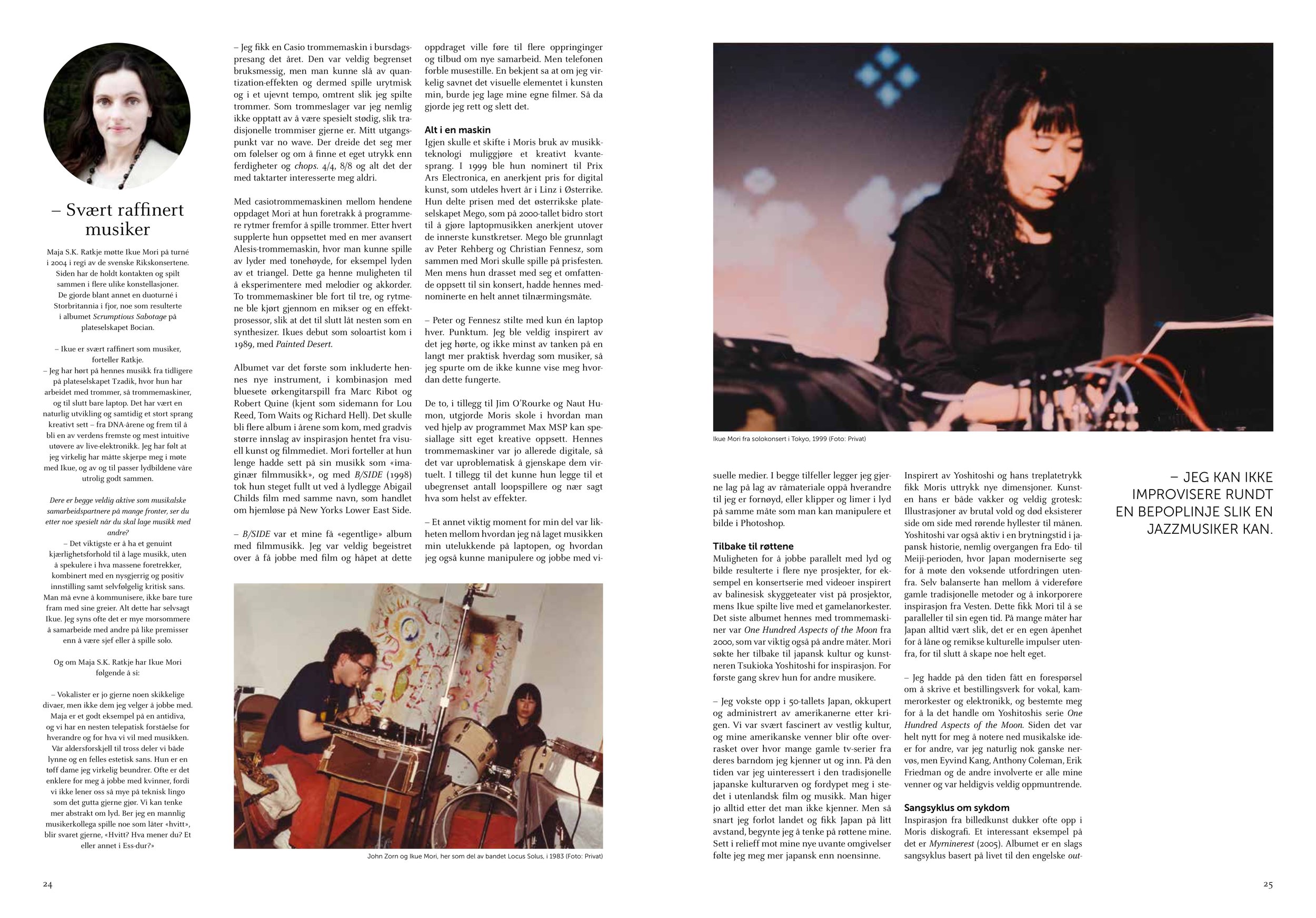

Alt kan ikke planlegges (Everything cannot be planned for), An interview with no wave musician Ikue mori – ENO Music magazine, 2013 (in Norwegian)

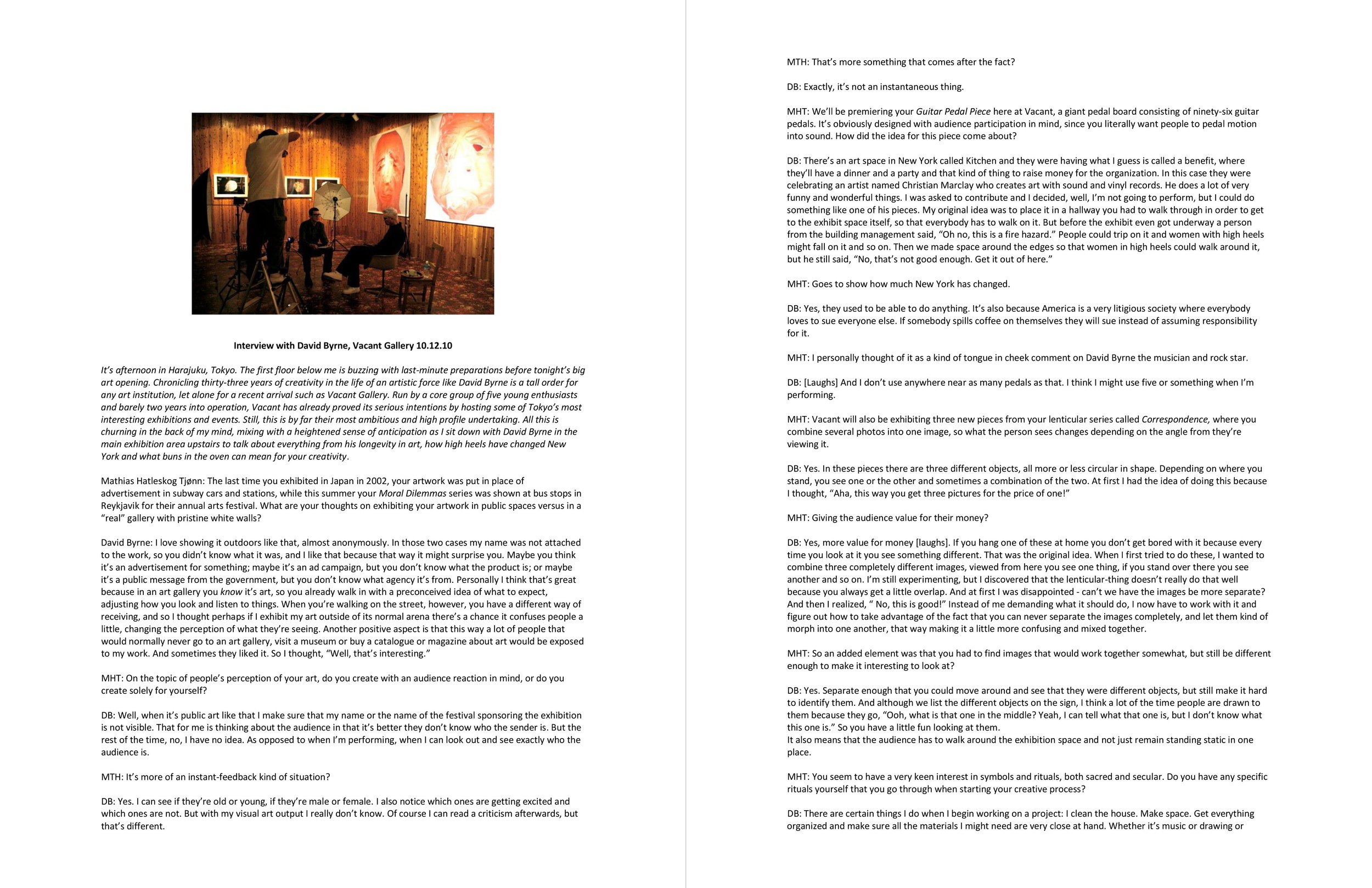

An interview with David byrne for his art exhibit at VACant gallery in Tokyo, Japan, 2010